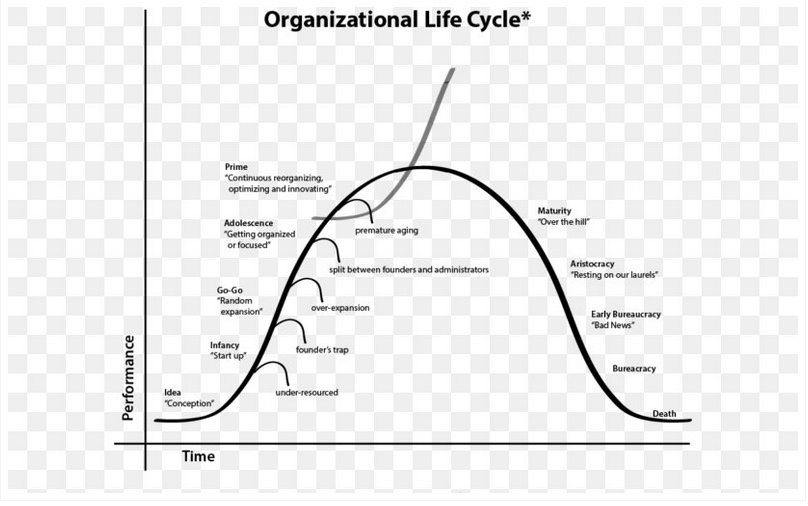

With more than 1.5 million nonprofits in the United States, all of them at varying stages of development or decline, it behooves nonprofit leaders and managers to be mindful of organizational lifecycle models and dynamics. Because while some challenges facing nonprofits are “stage-invariant” (i.e., they demand continuous attention regardless of an organization’s lifecycle stage), others are “stage-variant,” meaning that unique challenges are encountered as organizations transition from one stage of their lifecycle to another (for example, from conception to start-up, from entrepreneurial leadership to professional management, etc.).

Image from righttojoy.com

While it is beyond the scope of this article to deal with the unique challenges that accompany specific stages in an organization’s development or decline, serious readers may take comfort in knowing that a substantial body of literature is available on the topic. In this article, I merely want to introduce key concepts and principles that have served me well in work with a great many organizations over several decades.

Change

In a 2011 national research project I conducted entailing interviews with 60 CEOs and CDOs (chief development officers) of leading U.S. ministries, these leaders revealed that the greatest challenge they faced was leading and managing change in wide variety of forms.

When asked what the greatest unmet need of their organizations was, it came as no surprise that funding topped the list. Funding is mentioned here because while essential to every organization, the availability of funding will generally be a function of how well organizations manage their lifecycle dynamics and the specific challenges characteristic of different lifecycle stages. In the parlance of high performance jet aircraft pilots, serious mistakes here can be “non-habit forming.”

Let’s begin this discussion, then, with the understanding that inherent in the concept of lifecycles is change. This change comes in a bewildering assortment of flavors: personal, family, team, organizational, social, technological, demographic, economic, wanted, unwanted, voluntary, coerced…the list could go on.

To keep things reasonably simple (heeding Einstein’s admonition to “keep things as simple as possible but no simpler”), it has been helpful for me as a change consultant to diagnostically “sort” the challenge of changes faced by organizations into three broad categories:

- Developmental – Although generally accompanied by growing pains, developmental change is routinely positive. It is typically the type of growth-induced change that is sought by nonprofits to increase the impact of their work.

- Transitional – This type of change frequently comes as a result of leadership succession, especially in: the passing of the baton from a founder to a new generation of leadership; mergers of smaller ministries with other similar organizations in the pursuit of sustainability and/or synergy; and in rebranding efforts to achieve and sustain relevance with new generations of stakeholders, especially donors or other funders or critical resource providers.

- Turnaround/Transformation – The type of deep change involved in turning around stagnant, declining, or failing organizations.

In addition, I have found it helpful initially to assess organizations not only in terms of the type of change they are confronting, but also the depth of change needed. In progressive levels of depth, I call these the “3 Rs“:

- Revitalization (working to restore “the juice” when the fizz has gone flat);

- Renaissance (working to achieve a rebirthing of organizations where revitalization alone will prove inadequate); and,

- Reinventing (radical and comprehensive transformation needed to rescue organizations that have become perilously and perhaps even fatally misaligned with market and operating realities).

Tools for the Toolkit

Many years ago I learned from Dr. Warren Wiersbe a proverb that reflects wisdom we would all do well to heed: “Methods are many, principles are few. Methods always change, principles never do.” With that in mind, rather than sharing specific methods, let me share 10 key concepts and principles that inform my thinking about leading and managing change regardless of the lifecycle stage an organization may find itself in.

- Disequilibrium – Disequilibrium is essential to change. No disequilibrium, no change. Given the natural tendency of humans (like other living systems) to seek equilibrium, many organizations – especially those that by nature are conservative in their DNA – tend eventually to get “stuck.” As organizations drift, often unconsciously, into organizational dry rot and other arthritic states, disequilibrium will need to be induced to facilitate significant movement. This is often a key challenge of leaders: finding just the right combination of WD-40 and dynamite to release the brakes and begin movement in a positive direction. Miscalculate the amount of disequilibrium required – too much or too little – and change will falter.

- Resistance to Change – Understand that while not all change will be resisted, all significant change initiatives will face varying degrees of resistance. The Principle of Resistance to Change states, “The greater the proposed departure from existing ways, the greater the resistance.” Practically speaking, this means that when organizations have the luxury of taking change incrementally, these initiatives will predictably be met with less resistance. Bold change initiatives, while applauded by some, will almost invariably be met with greater resistance from others.

- Change vs. Transition – As William Bridges has insightfully noted (Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change), “change” is the external stuff, “transition” is the internal stuff. “Internal” here means the psychological and emotional responses of individuals to change. As Bridges notes, “It isn’t the changes that do you in, it’s the transitions.” Many change initiatives fail because so much focus was placed on external “objective” and “rational” demands that critical subjective and emotional transition demands were overlooked or mismanaged.

- Urgency: The Burning Platform – Just as we might say regarding disequilibrium, “No disequilibrium, no change,” so with urgency we might say, “Little urgency, little change.” This is often merely a variant of Parkinson’s Law: that a task expands to fill the amount of time allotted to it. For those organizations facing the imperative of change, a compelling vision for change is often not enough. Some people change just as soon as they see the light (i.e., the need for change) — while others are what I call “thermo-luminals” — they see the light only when they feel the heat! The metaphor of the burning platform, popular among change agents, recalls a true incident in 1988 in the North Sea when a man named Andy Mochan, a superintendent on an oil platform, was suddenly awakened one night by an explosion. As a huge ball of fire billowed behind him, he decided to jump to the turbulent waters below despite the risks. These entailed a 150-foot drop to the water, dangerous debris and burning oil on the surface, and the fact that if the jump into the 40 degree water didn’t kill him, he would likely die within 15 minutes from exposure. Luckily, Mochan was hauled aboard a rescue boat. When asked why he jumped he said, “Better probable death than certain death.” The point? Simply that the demands facing some organizations today are akin to a burning platform. For these organizations, we might paraphrase Shinseki and say, “If you don’t like change, you’ll like extinction even less.”

——- § ——-

“If you don’t like change, you’ll like irrelevance even less.”

— General Eric Shinseki

——- § ——-

- Vision – Despite forests of paper and oceans of ink having been consumed on the topic of vision, many organizations sadly still don’t get it. Paradoxically, they may have vision statements, but no real vision. A genuinely compelling vision of an attractive future – shared by a critical mass of key stakeholders – is crucial to all major change initiatives and change leaders gamble dangerously if insufficient time and thought are given to crafting and relentlessly communicating this vision.

- Attunement and Alignment – Attunement entails the leadership function of mobilizing and amplifying the spiritual, psychological, and emotional resources of the organization. Alignment involves not only understanding the concept of alignment, but having an explicit alignment model and process to guide change initiatives.

- Involvement – In a nutshell, people tend to support what they help to create. My formula says, “No involvement = no ownership. No ownership = no commitment.” Because there is a vast performance differential between mere compliance and true commitment when it comes to execution, the Involvement Principle points to the need, where possible, to involve in change initiatives those who will be impacted by the change.

- Holistic vs. atomistic – Most change on a significant scale more closely parallels holistic medicine than piecemeal, organ-by-organ transplants. This principle of holism reminds change agents to keep the bigger picture in mind and to recognize crucial interdependencies in change efforts. A well-known critical interdependency that requires continuous alignment is the link between strategy and culture. Peter Drucker’s now popular adage — “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” — underscores the criticality of avoiding a tunnel vision that neglects vital interdependencies in change initiatives.

- Metrics – Savvy managers understand The Measurement Principle: “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” and “What gets measured gets done.” Successful change managers grasp the criticality of key metrics to inform and guide change and the power of smart metrics to sustain a focus on change essentials.

- Recognition and Rewards – Just as it’s true that “what gets measured gets done,” so is it true that “what gets rewarded gets done.” If I have only two possible interventions to bring about change in an organization, I would change what is measured and change what is rewarded.

Clearly, these concepts and principles – as tools for your toolkit – are rarely used alone. They are generally used creatively and synergistically to either sustain growth and development through the various stages of organizational lifecycles, or to restore health and vitality to organizations that have entered stages of stagnation and decline.

In our current VUCA environment (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) that has been characterized as “permanent whitewater,” management guru Tom Peters has suggested that we eliminate “change” from our vocabularies and substitute “revolution.”

With technological, social, and cultural revolutions showing no signs of subsiding, I concur wholeheartedly with Eric Hoffer:

——- § ——-

“In a time of drastic change it is the learners who inherit the future.

The learned usually find themselves equipped

to live in a world that no longer exists.”

——- § ——-

________

If your organization is seeking a path through the wilderness of change, welcome aboard. Feel free to reach me at drlarryjohnston@aol.com or call me at 303.638.1827 for a complimentary path finding consultation. We’ve been helping Christian organizations of all sizes for 40+ years to grow and excel and would welcome the opportunity to explore how we might help you and your organization. www.mcconkey-johnston.com

Larry F. Johnston, PhD is president of McConkey • Johnston International.